We ventured into our 42nd national park with no previous knowledge about what makes it special… and left with a great appreciation of the beauty and heritage of Congaree National Park, located about 20 miles southeast of Columbia, South Carolina.

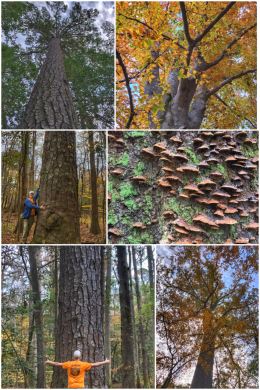

We wondered how many people were aware of this 26,276-acre gem located in central South Carolina… which only became a national park less than 20 years ago in 2003. Interestingly, about 15,000 acres of the park are designated as wilderness. This grand national park preserves the largest tract of old growth bottomland hardwood forest (about 11,000 acres) left in the entire United States. In fact, it has numerous state and national champion trees (currently about 25 of them) within its boundaries and is known for having some of the tallest in the east — including a 167-foot tall Loblolly Pine (Ran’s favorite; seen hugging in the collage below), 162-foot Swamp Tupelo, 157-foot Sweetgum, 154-foot Cherrybark Oak, 145-foot Shumard Oak, 135-foot American Elm, 133-foot Swamp Chestnut Oak, 130-foot Laurel Oak, 127-foot Bald Cypress, and a 127-foot Common Persimmon. Several bald cypress trees in the park are more than 500 years old! (Fun fact: champion trees are scored on three criteria: height, trunk circumference, and crown spread.)

One might ask, why there are so many big trees here? Thanks for playing along. The park has the perfect recipe for big and tall trees: first, a relatively long and warm growing season; second, lots of nutrients are continually added to the soil from the annual floodings of the land by the Congaree and Wateree Rivers; third, many of these trees were simply too deep into the woods and swamp to harvest, which allowed them to continue growing.

The land was originally saved from timber barons who harvested many of the surrounding forests when Congress created the Congaree Swamp National Monument in 1976. (Numerous national parks we have visited started out as national monuments.) When the park was re-designated by Congress as a national park in 2003, it dropped swamp from the name because the word is misleading… while parts of the area may be swampy, the area is largely bottomland subject to periodic inundation by floodwaters during winter months. This land was preserved in the nick of time too because at one point there were more than 35 million acres of old-growth floodplain forests; today, 99 percent of these forests are gone — harvested because of demand for timber for railroads, ships, and building construction.

We, of course, started at the visitor center… officially the Harry Hampton Visitor Center. (Harry R.E. Hampton, a South Carolina journalist and conservationist, was a key figure in fighting to have the land protected and preserved for future generations; it is amazing how many of these wonderful lands are now parks or monuments thanks to the efforts of a single person leading the fight.)

After a wonderful chat with a ranger, we watched the park’s movie — which quickly became one of our favorites of the 40+ we have watched over the past two years; it was informative, evocative, and emotionally satisfying. We then bought a magnet (and bat pin for Ran’s hat) before getting our hiking gear from the truck.

We decided to combine two trails for one long hike, starting with the park’s most popular trail — and from which most of the other trails originate — the 2.4-mile Boardwalk Loop Trail, which is an amazing journey into parts of the old growth forest… where you’ll encounter Bald Cypress (with those crazy “knees” that rise above the ground like sentinels) and Tupelo trees in the lowest elevations and Loblolly Pines, Oaks, Maples, and Holly trees in slightly higher (and drier) elevations. Before heading out onto the trail, make sure you get a brochure that highlights 20 key things along the trail. Two interesting facts about this trail: it is 100-percent accessible (though portions of the trail will be closed this winter as construction is done on improving sections of the boardwalk) and every winter portions of the boardwalk get completely submerged by the annual flooding (which can reach up to 8 feet in certain low-lying areas).

We exited the Boardwalk Trail briefly to also hike the 4.4-mile Weston Lake Loop Trail, which offers nice vistas of Cedar Creek as well as following along a cypress-tupelo slough (pronounced slew) — a low channel that helps disperse water throughout the floodplain. (Also referred to as a gut.)

Back on the Boardwalk Trail, we continued our journey back toward the visitor center, passing an old still used to make moonshine during Prohibition, as well as learning more about the history of escaped slaves who formed maroon settlements deep in these forest wetlands — too far in to be found, and starting their journey to freedom.

Other trails in the park include: Bluff Trail (1.7-miles RT), Sims Trail (3.2-miles RT), Oakridge Trail (7-miles RT), River Trail (10.4-miles RT), and Kingsnake Trail (11.7-miles RT).

Other activities in the park include birding, camping, and boating (by canoe or kayak only). If you have the equipment, you can launch your canoe or kayak along a stretch of Cedar Creek that the park service keeps open and clear (from falling trees). If you’re like us, you can use one of several park-approved outfitters to guide you down the creek. Many only operate seasonally and on weekends; we happily found Carolina Outdoor Adventures, which offers a variety of trips along Cedar Creek and the Congaree River.

Billy Easterbrooks, the founder and main guide for Carolina outdoor Adventures, is a fun and friendly guy (who also happens to respond quickly to emails). We love that he added a Friday tour to enable us to kayak down (and back up) the creek.

We met up at the Cedar Creek Landing and paddled for about 3 miles — or about the only length completely cleared of debris by the park service. We traveled downstream to Dawson’s Lake,

an oxbow created when the Congaree River changed course many, many years ago — and now a very popular place to fish. We then traveled a little ways up one of the many guts located along the creek before turning back upstream. Happily, this time of year there are few snakes along the creek, but Billy told us that in the spring and summer snakes often drop from the hanging branches of trees right into people’s canoes/kayaks; the vast majority of these snakes are nonvenomous.

Especially for Jen, we were also delighted to discover that the park’s Mosquito Meter (shown in the first collage) rated only a 1.5 (mild) — and in fact, we did not encounter any of those nasty bloodsuckers on our hikes nor while kayaking. It’s a bit scary to think about encountering the 6 rating (war zone).

There’s also another access point for Cedar Creek (near the confluence of Cedar and Myers Creek) on the very west end of the park at Banister’s Bridge Landing — and one could in theory canoe or kayak the six miles all the way down to the Cedar Creek Landing, but the creek is uncleared in many spots along this stretch and would require exiting the creek and carrying equipment around the obstacles.

After kayaking, we decided to also hike some of the Kingsnake Trail — which has a trailhead at Cedar Creek Landing. We stopped long before the trail connects to the Weston Lake Loop Trail!

The Congaree River dominates this park — and, of course, the park was named for the river. In turn, the river was named for the Congaree — a native people who, according to archaeological evidence, had been inhabiting the area for thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans… and their eventual displacement.

For anyone living on the east coast, this park should be a priority to visit… but really, for all tree lovers, it is a must-see! The park also boasts the chance to see river otters, feral (and invasive) hogs, deer, squirrels, and many species of birds. But one of the big highlights for many is the annual Firefly Festival — a 10-day event typically in May that offers the opportunity to witness a synchronous fireflies phenomenon, an awe-inspiring display of synchronous flashing while the fireflies search for a mate. (There are only three species of synchronous firefly species in North America.)

Next up? Exploring the rest of South Carolina.

One comment