We spent several, very soggy and humid days, in the Biloxi/Gulfport area of the Mississippi Gulf Coast in the southeast part of the state, #17 on our amazing road trip, exploring the area while also taking care of some business and schoolwork.

Note to others considering this area. Ran did not realize that this area is like a miniature Las Vegas — which means higher prices, clogged roads, and lots of casinos — 11 altogether between Biloxi and Gulfport.

Happily, a chunk of our time was spent exploring some of the natural spots in the area, including another favorite wildlife refuge — the Mississippi Sandhill Crane National Wildlife Refuge, located near Gautier, about 20 miles northeast of Biloxi. The 19,000-acre refuge was established in 1975, part of a reaction to a lawsuit over the endangered Mississippi Sandhill Crane that saw its numbers dropping sharply to as few as 30 (with only 5 breeding pairs) as development and commercial forestry eliminated its natural wet pine savanna habitat. (Less than 5 percent of the original acreage of this habitat now remains in the Atlantic/Gulf Coast Plain — with one of the last remaining large patches protected by the wildlife refuge.) These cranes are extremely rare — and are found nowhere else on Earth in the wild.

While there are 15 species of cranes in the world — found on all continents except South America and Antarctica — 11 of those 15 are considered at risk for extinction. Two cranes species are found in North America — the endangered whooping crane and the wide-ranging sandhill cranes. The Mississippi Sandhill Crane is a non-migratory subspecies of the wide-ranging sandhill cranes.

These beautiful Mississippi Sandhill Cranes, which mate for life, are slowly gaining in numbers through a combination of habitat protection and a breeding/hatching program, with about 100+ cranes now living in the wildlife refuge. Interestingly, some other migratory Greater Sandhill Cranes often spend time during winter months at the refuge — but the two species do not interbreed.

Besides the cranes, of course, numerous other birds (including Henslow’s Sparrow, Yellow Rail, and Prothonotary Warbler) and animals also live in the refuge. Perhaps even more interesting, ten species of carnivorous plants grow in the refuge (including bladderworts, butterworts, sundews, and pitcher plants).

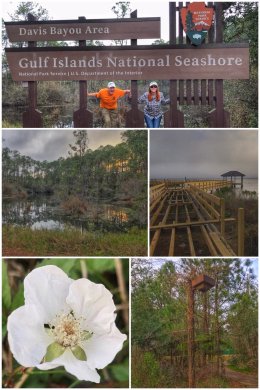

Much of the refuge is off-limits to people (to protect the cranes), but we found ourselves enjoying the .75-mile C.L. Dees Trail, which can be found across from the visitor center. (By the way, yes, the center offers a great educational and fairly short video on the cranes.) The nature trail winds its way through pine savanna, tidal marsh, and pine scrub — and offers views of the Bayou Castille.

Another refuge trail can be found south of the main center, off Hanshaw Road. The 1+ mile (depending on the loop/options) Fontainebleau Trail includes several overlooks as you hike through the Davis bayou — into pine flatwoods, seepage bogs, and bottomland hardwoods.

Finally, in the fall and winter months, you can reserve a free spot to go on “safari” with a ranger to try to get closer to the elusive, but beautiful birds!

A few mile drive from the Fontainebleau Trail, is the Davis Bayou Area of the Gulf Islands National Seashore — the only mainland area of the national seashore in Mississippi — offering views of the bayou and Mississippi Sound (including several barrier islands). The William M. Colmer Visitor Center offers exhibits, a small gift shop, and a film… though the day we visited, the projector bulb was burnt out so we cannot speak to the quality of the film.

The Gulf Islands National Seashore extends 160 miles from Mississippi to Florida — so we will visit it again later in our journey. The park was established in 1971 to protect the barrier islands, bayous, maritime forests, marine habitats, historic structures (including forts), and other archaeological sites along the Gulf of Mexico — and covers more than 139,000 acres (about 82 percent submerged under water), making it the largest national seashore in the U.S. It protects five species of sea turtles, and 345 species of birds, as well as alligators and other animals.

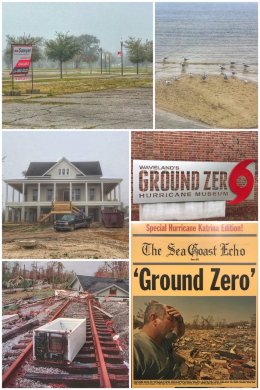

We ended our murky stay in the Biloxi area with a stop at the Waveland Ground Zero Hurricane Museum, which documents the total devastation — and slow, but amazing recovery — from the impact of what some people call the worst natural disaster in U.S. history: the massive Hurricane Katrina in 2005 with its extreme winds and tsunami-like surge that took dozens of lives and destroyed tens of thousands of homes across the coast… leaving behind unprecedented devastation and heartbreak. The building that houses the museum, an old schoolhouse built in 1927, was the only building not destroyed by the storm surge on Coleman Avenue, the historic main street of Waveland. The museum not only documents the jaw-dropping destruction from Katrina, but also serves as a tribute to the strength and beauty of the human spirit — both in the residents who persevered, but also the thousands of volunteers who aided in the recovery.

All along the Mississippi coast we saw dozens and dozens of empty lots… driveways leading to nowhere — and tons of “for sale” signs. Some homes have been rebuilt, but many have not. The high cost of building a new home on the coast — including requirements in some places for the houses to be built high above ground — as well as prohibitive insurance costs have kept many people from rebuilding.

We now head upstate and through Mississippi, and hopefully away from all the fog and humidity, as we begin the next phase of our adventure.