We made a quick dash back to Pennsylvania so that we could visit two historic sites — one related to the Revolutionary War and the other to the Civil War… settling in at a very small, but interesting campground in York.

We started this adventure in Valley Forge, located about 24 miles northwest of Philadelphia, and the site of a Revolutionary War encampment in 1777-1778 by George Washington, his top aides, and thousands of Continental Amy troops. At the time of the encampment, some 1,500 log huts and miles of fortifications were built in Valley Forge. Back then, the British occupied Philadelphia and with the Continental Congress fleeing to York, Washington chose Valley Forge for its close (a day’s travel) proximity to Philadelphia, but also counting on the winter weather to slow down the fighting.

Washington used the time to regroup and retrain the troops into a more unified (united) fighting force — moving toward an allegiance to the United State versus their home states… along with a organized fighting force.

The 3,500-acre park contains historical buildings, recreated encampment structures, memorials, museums, and recreation facilities. Valley Forge was designated a U.S. National Historic Landmark in 1961 and was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1966. It includes an auto trail and 26 miles of hiking trails. We took the auto tour and enjoyed stops at the National Memorial Arch and Washington’s Headquarters (both shown in the photo collage above). At Washington’s Headquarters, we met up with one of those park rangers who are entertaining and informative — a true gem, but one we had to eventually escape while it was still daylight!

Of course, we started our visit in the temporary visitor center and watching the 18-minute film, “Valley Forge: A Winter Encampment.” (The main visitor center is undergoing renovations and will reopen in 2020.) Overall, we enjoyed the visit and the renewed history lessons of the Revolutionary War.

The park has several options for trails, including The River Trail (3 miles), which we hiked, as well as the Joseph Plumb Martin Trail (8.7 miles), Chapel Trail (2.5 miles), and Valley Creek Trail (1.5 miles).

The next day we took advantage of some beautiful weather and amazing luck to get back on our bikes to ride part of the 21-mile York County Heritage Trail, a National Recreation Trail, which we accessed right from our campground. (We had actually “lost” our bikes on the way to York when both u-bolts failed on our trailer bumper hitch and the bike racks and bikes went sailing; amazingly, some wonderful RVers from Maryland not only put our bikes on the side of the road, but caught up with us when we had pulled over to tell us where we could find the bikes… so thankful for thoughtful and kind people and amazed the bikes survived with just a few minor scraps and scratches.)

The rail-trail is interesting because the trail runs along an existing rail line — originally developed by the York and Maryland Line Rail Road for use by the Northern Central Railway (which was later acquired by the Pennsylvania Railroad) — on what used to be the second track before the it was removed. The current track is still “active,” used seasonally by a Civil War-themed tourist railroad called Steam into History. The railroad was originally developed as a key trade/distribution link between Washington, D.C., Harrisburg, PA, and upstate New York (to Lake Ontario).

The trail is quite lovely, especially in autumn, with the leaves of the trees shimmering in mostly yellows and greens and with lots of leaves already scattered along the trail. The section we rode was mostly rural and scenic, following the banks of Codorus Creek. Along the ride, we saw cows in pastures on both sides of the trail.

More fascinating than its beauty, though, is the history of these tracks and the railroad that once used them. For example, we ended our bike ride at Hanover Junction Railroad Station, which served as a major communications depot between Gettysburg and Washington, D.C., during the Civil War. President Abraham Lincoln also changed trains here on his way to deliver the Gettysburg Address! The depot, while closed when we visited, has bathrooms and a museum. Another example is the 370-foot-long brick-lined Howard Tunnel in Seven Valleys, a stone-arch tunnel that was built in 1838, and is one of the oldest in the country. During the Civil War, the Union Army posted canons on the top of it to protect it from Confederate Army troops trying to blow it up. In 1868, after the war, the tunnel was rebuilt to accommodate two tracks. In 1990, York County acquired the tunnel and rail corridor. In 1995, the tunnel was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

We considered some wine-tasting along the Mason-Dixon Wine trail located in the York-Hershey-Lancaster area, but we had more important things to accomplish — including our next adventure.

Gettysburg and the Civil War

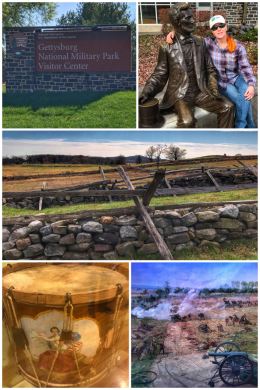

The next day it was time to immerse ourselves into some Civil War history by visiting Gettysburg National Military Park. The 3,965-acre park protects and educates about the July 1-3, 1863, multiple-day battles in Gettysburg when the Confederate Army led by General Robert E. Lee, sensing a chance to make a major statement and turn the tide of the Civil War with a victory in a “northern” state, decided to attack the Union Army. After three days of fierce fighting, the Union Army held their ground and and Lee and the Confederate army retreated back into Virginia. The battles caused the largest number of casualties of the entire war and is described as a key turning point in the war — even though it raged on for several more years.

Just four months later, on November 19, President Abraham Lincoln dedicated the Soldiers’ National Cemetery (much needed to address all the men who had died on the fields of Gettysburg) and delivered one of the iconic presidential speeches in the Gettysburg Address.

We started our exploration of the park at the visitor center, which is very large — for several interesting reasons. We chatted with a ranger and got a feel for the auto tour and trails and purchased our tickets for the movie (narrated by Morgan Freeman), A New Birth of Freedom, as well as entry into the very amazing and quite unique Gettysburg Cyclorama. The cyclorama is a sound and light show of the 377-foot long and 42-foot high oil painting by French artist Paul Phillippoteaux depicting Picket’s Charge, the third and final (failed) Confederate attack on Union forces. The cylindrical painting was completed in 1884; it took more than a year and a half to complete — and when done the painting was nearly 100 yards long and weighed six tons. These types of 360-degree paintings were designed to immerse viewers into the action with panoramic views. The visitor center also houses a museum, which you can enter separately, or in combination with the movie and cyclorama. It has 22,000 square feet of exhibit space and holds once of the most extensive collections of Civil War relics.

FYI, the museum and visitor center is owned and operated by the Gettysburg Foundation, which has fees for everything in the park. The Gettysburg Foundation is the non-profit philanthropic, educational organization operating in partnership with the National Park Service to preserve Gettysburg National Military Park and Eisenhower National Historic Site — and to educate the public about their significance.

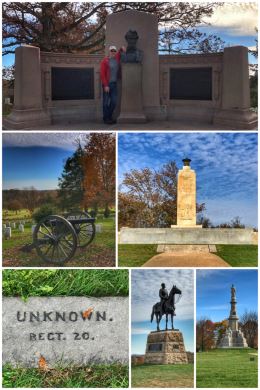

After the visitor center, we decided to hike the 1.5-mile Cemetery Ridge Trail. Just north of the trail is the Gettysburg National Cemetery and Soldiers’ National Monument, which contains the 3,512 interments from the Civil War, including the graves of 979 unknown (mostly Confederate) soldiers. After the war concluded, some 3,320 Confederate soldiers were removed to cemeteries in the south.

It’s at this cemetery where President Lincoln made the dedication, delivering the Gettysburg Address. (Lincoln was NOT the featured speaker; Edward Everett, one of the great American orators of the time, delivered a two-hour speech prior to Lincoln.) While we knew of the address and had learned even more about it when we were in Illinois visiting Lincoln’s home and tomb, we had never known the exact reasoning behind the speech. The speech is short (just 271 words), but iconic — and we include it at the end of this post.

It is quite something to walk these sad, yet hallowed grounds — a place where all these battles took place, trying to imagine the sounds from all the cannons and gun fire… the cries of the wounded… the bodies of young men so thick that it blocks your vision of the ground. These battles were fierce — and so unnecessary… and for so many, sadly, some of the distrust and hate is still felt today.

We ended our time in Gettysburg at the Eternal Light Peace Memorial, in the northern section of the park. Dedicated on July 3, 1938 — 75 years to the date on which one of the last battles on McPherson and Oak ridges took place — and with some 1,800+ Civil War veterans in attendance, this monument speaks of “Peace Eternal in a Nation United.” A natural-gas flame burns brightly in one-ton bronze urn — atop a tower on a stone pedestrian terrace on top of the ridge.

Gettysburg Address

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.