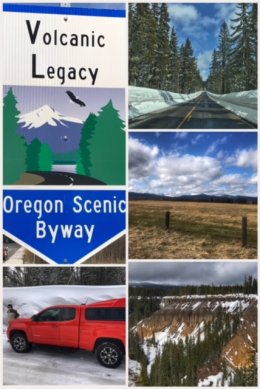

Ah, the Pacific Northwest in all its glory… that was the theme of this, our 20th stop, on this 2-year+ journey across the continental United States. It also was the continuation of our journey along the Volcanic Legacy Scenic Byway… including a stop at National Park #10 on our list: Crater Lake National Park, established in 1902.

Ah, the Pacific Northwest in all its glory… that was the theme of this, our 20th stop, on this 2-year+ journey across the continental United States. It also was the continuation of our journey along the Volcanic Legacy Scenic Byway… including a stop at National Park #10 on our list: Crater Lake National Park, established in 1902.

We planned several days for this stop, partly because we wanted to explore the surrounding forests and lakes, but also because the winter weather at Crater Lake is very changeable… and we wanted to have flexibility on visiting on the best day. (We recommend using the Park Service webcams to help you, but in reality, you may simply have to wait things out.) Because it is a big bowl, weather systems seem to like to stop and hover for a while.

We stayed at a cute little RV park, appropriately named Big Pines, located in Crescent, Oregon, a veteran-owned and operated RV park that is on the site of an old motor motel that offered roadside cabins (with indoor plumbing). Some of the original cabins still stand, including one that is a very nice shower/bath facility. The park is conveniently located about half way between Bend and Crater Lake, with all sorts of outdoor activities nearby. One of the other features we loved is a collection of ORV trails behind the park that made for pleasant hikes during the times we were working and needed a little nature break.

We stayed at a cute little RV park, appropriately named Big Pines, located in Crescent, Oregon, a veteran-owned and operated RV park that is on the site of an old motor motel that offered roadside cabins (with indoor plumbing). Some of the original cabins still stand, including one that is a very nice shower/bath facility. The park is conveniently located about half way between Bend and Crater Lake, with all sorts of outdoor activities nearby. One of the other features we loved is a collection of ORV trails behind the park that made for pleasant hikes during the times we were working and needed a little nature break.

The biggest surprise for us was discovering that several lakes and rivers and the Cascade Lakes National Scenic Byway, all within the Deschutes National Forest, were located just north and west of the RV park. You’ll find beautiful forests, crystal-clear alpine lakes, and striking volcanic landscape along this 66-mile scenic drive. We drove the southern half of the biway, saving the other half when we circle around and visit the Bend, Oregon, area in a few weeks. Do stop at Davis Lake, formed when a lava flow blocked Odell Creek about 6,000 years ago — and take a moment to stop and read about the intense and massive wildfire that scarred the whole area back in 2003; Wickiup Reservoir, which has the most beautiful green — a cross between aquamarine and emerald green; Crane Prairie Reservoir, a man-made lake named for the cranes that once flourished here, and which offers great rainbow trout fishing; and North and South Twin Lakes, two nearly identical circular lakes formed when a rising magma reservoir reached groundwater about 20,000 years ago, a unique geological formation known as volcanic mars.

The biggest surprise for us was discovering that several lakes and rivers and the Cascade Lakes National Scenic Byway, all within the Deschutes National Forest, were located just north and west of the RV park. You’ll find beautiful forests, crystal-clear alpine lakes, and striking volcanic landscape along this 66-mile scenic drive. We drove the southern half of the biway, saving the other half when we circle around and visit the Bend, Oregon, area in a few weeks. Do stop at Davis Lake, formed when a lava flow blocked Odell Creek about 6,000 years ago — and take a moment to stop and read about the intense and massive wildfire that scarred the whole area back in 2003; Wickiup Reservoir, which has the most beautiful green — a cross between aquamarine and emerald green; Crane Prairie Reservoir, a man-made lake named for the cranes that once flourished here, and which offers great rainbow trout fishing; and North and South Twin Lakes, two nearly identical circular lakes formed when a rising magma reservoir reached groundwater about 20,000 years ago, a unique geological formation known as volcanic mars.

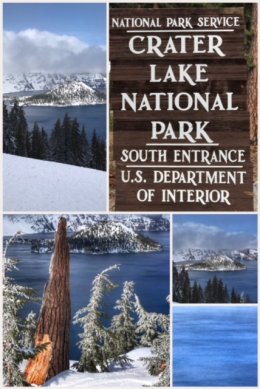

The main purpose of this stop, of course, was a visit to Crater Lake… which seemed questionable for a while given a weather forecast of rain and snow for most of the days of our visit. During “winter” months (which can last until July), only the south entrance to the park is plowed and open, with limited access to the Rim Road area. Noting this issue, we plan to revisit the park in September/October of some future year… so that we can experience its beauty before the snow covers it, including many of the hiking trails and driving the rim road. But the winter season is fun too, and there are ski trails, and opportunities for snowshoeing, sledding, and snowboarding.

The main purpose of this stop, of course, was a visit to Crater Lake… which seemed questionable for a while given a weather forecast of rain and snow for most of the days of our visit. During “winter” months (which can last until July), only the south entrance to the park is plowed and open, with limited access to the Rim Road area. Noting this issue, we plan to revisit the park in September/October of some future year… so that we can experience its beauty before the snow covers it, including many of the hiking trails and driving the rim road. But the winter season is fun too, and there are ski trails, and opportunities for snowshoeing, sledding, and snowboarding.

Crater Lake, with a depth of 1,943 feet, is the deepest lake in the U.S., and one of the deepest in the world…. and certainly one of the most beautiful blue lakes ever. The water in the lake is clear and pure — mainly because it comes completely from rain and snow. The lake is a caldera — the basin of a collapsed volcano — and contains about 4.9 trillion gallons of water. The whole process began about 7,700 years ago when the giant (12,000+-feet) Mount Mazama (part of the Cascade Range volcanic arc) erupted — and, amazingly, blew holes in an almost circular pattern, resulting in the top of the mountain collapsing into the magma chamber. Wizard Island, perhaps one of the most photographed features of Crater Lake, is actually a volcanic cinder cone.

Luck was with us on the day we visited; it had snowed the night before and the rim road was closed for half a day while they worked to clear the snow. But by the time we arrived, the snow had been cleared and we actually had some blue sky — before the clouds quickly returned; we left as it began to snow again. The temperature at the rim was 31 degrees, with a very cold, blustery wind! Still, we thoroughly enjoyed hiking around part of the rim, marveling at the beauty of the snow-covered trees and the deep blue of the lake.

Luck was with us on the day we visited; it had snowed the night before and the rim road was closed for half a day while they worked to clear the snow. But by the time we arrived, the snow had been cleared and we actually had some blue sky — before the clouds quickly returned; we left as it began to snow again. The temperature at the rim was 31 degrees, with a very cold, blustery wind! Still, we thoroughly enjoyed hiking around part of the rim, marveling at the beauty of the snow-covered trees and the deep blue of the lake.

The lake itself is only about 10 percent of the entire park. Beyond the lake, the park protects watersheds and old-growth forests — including 15 species of conifers, from Ponderosa Pines to Whitebark Pines. It helps, too, that the national park is nearly surrounded by several national forests, including the Winema National Forest, Rogue River National Forest, and Umpqua National Forest

By the way, the story of how Crater Lake came to be protected should be an inspiration to all of us — how one person can make a major impact. William Gladstone Steel, who is said to have seen a picture of Crater Lake during his childhood, finally got to see the lake in person in his early 30s… and then spent 17 years campaigning the U.S. Congress to protect it. His lobbying efforts paid off when Crater Lake was named the nation’s sixth national park — with some assistance from President Teddy Roosevelt, who helped lobby for the bill that established it. Steel’s picture sits on the hearth in the video room of the Steel Visitor Center.

By the way, the story of how Crater Lake came to be protected should be an inspiration to all of us — how one person can make a major impact. William Gladstone Steel, who is said to have seen a picture of Crater Lake during his childhood, finally got to see the lake in person in his early 30s… and then spent 17 years campaigning the U.S. Congress to protect it. His lobbying efforts paid off when Crater Lake was named the nation’s sixth national park — with some assistance from President Teddy Roosevelt, who helped lobby for the bill that established it. Steel’s picture sits on the hearth in the video room of the Steel Visitor Center.